First, the Cary-Yale. What I see is heraldics rather than hieroglyphs. Heraldics answer "who" questions, about actual people; hieroglyphs answer "what" question.It's not important, for example, what the red man being eaten by the dragon or snake means, but rather what family it represents.(If anyone knows Frege's "Sinn und Bedeutung," that's roughly the distinction I have in mind.) Often the heraldics are ambiguous even on that account, certainly from the vantage point of the 21st century if not then as well. In the Love card, is the white cross on red background the heraldic of Maria of Savoy (1428), Bianca Maria Visconti (1441), or Francesco Sforza (1450)? All are possible--and the first is not ruled out even if, as is likely, the card is post-1440. Maria of Savoy was still Duchess of Milan,the latest to arrive there in a grand procession; also, the card might be a copy of an earlier version.

Other examples: Are the people on the Chariot card Filippo and Maria of Savoy, Filippo and Bianca Maria, or Francesco and Bianca Maria? And on the World/Fama card, is it Piccinino in the boat, or Filippo (visiting his mistress), or the Fisher King in the Arthurian romances, lame and reclusive like Filippo? (I still maintain that as a possibility, given the Arthurian illustrations done by the Bembo workshop around that time.) If the Fisher King, then the World card is becoming hieroglyphic, pointing perhaps even to a mystical allegory. And who are the three kings on the theological virtue cards? Perhaps it was clearer when the words could be made out. Otherwise, besides these "who" questions, everything is straightforward, employing iconographic conventions known to all. (I am assuming that the strip of cloth dangling from Death is a familiar wrapping of the dead, either from medieval practice, from accounts of Jesus's burial, or from accounts of Egypt already known among the people.)

When we get to the PMB, the "What?" question is more prominent, and the "Who?" is on the mythic level (as in the Fisher King, or the three kings), not the level of an actual contemporary person.

The PMB Fool looks like a fool, yet his feathers suggest a halo and the seven weeks of Lent (as I think Moakley pointed out). There was the tradition of the wise fool, which jesters were considered, and Cusa's "learned ignorance."

Then comes the PMB Bagatto. His table has a cloth covering something, but what? It looks like a Eucharistic cloth, but that doesn't fit the rest of the card. And do the objects represent the four elements as well as the four suits, and so the creator-god of this world of illusion and literary imagination? This is a question the common people would not be prepared for.

Next is the Popess. Is she a positive or negative character? Is she the Church positive or the Church negative? Is she Pope Joan, and if so, is that positive or negative? And for the Sforza family, there is also the ancestress, a more heraldic type of "who" in that it is a particular actual person, wearing a particular brown habit. Again, is she positive or negative? The answer is likely to be "both" in all cases, examples of Cusa's "coincidencia oppositorum.".It is hard to say what the common people would make of this card.

Empress, Emperor, Pope, and Love are like the Cary-Yale, but with fewer heraldic features. But the Empress and female Lover have their green glove, which might qualify as a hieroglyph, if the color was not known by all as a symbol of fertility.

The Chariot-lady is now not any of the particular people we might have imagined for the CY (although she still could be them, too). The wings on the horses identify her as ideal Beauty or one of the other idealized virtues in Plato's Phaedrus (247a-253c), upon whom the noble charioteer gazed before his own horses lost their wings, and which he remembers even after. For the Zeus-like nature, disposed to the "leading of men," she would be identified with Minerva, Wisdom (Phaedrus 252e); indeed, the orb and scepter were sometimes given to Minerva; she would be the "Minerva Pacifica" bringing peace after a hard-won victory. Whoever it is, it is an allegory known to the learned, although the unlearned would not be wrong in taking her as Chastity in the Petrarchan parades. Both goddesses--Celestial Venus as ideal Beauty, and Minerva as Wisdom--were chaste.

The Hanged Man is a beautifully ambiguous figure, like the Popess. Is he a traitor or someone unjustly accused, like the Sforza ancestor (who in fact did no wrong in deserting the anti-pope)? Is he Judas or Jesus, both considered traitors in their time, by the different sides? There is also a heraldic-like element in the reference to the Sforza ancestor.

Death remains non-enigmatic, and also Temperance and Star, except for who in the Sforza family the lady on these cards might have been meant to be--what I would call a "heraldic" issue; yet such identification is quite incidental to the meaning. But Moon is quite puzzling. It is like what would later be called an emblem, but without the verse to clarify things. The Sun card is not of a conventional figure known to all, nor is World/Fama (is the city supposed to be in this world or the next?); hence they are problematic, and I'm not sure which kind of enigma; whether they have a straightforward decoding or hint at deeper mystereis. Judgment is non-enigmatic.

The many-faceted, enigmatic cards (Fool, Bagatto, Popess, Chariot, Hanged Man, Moon, World, probably ohers), whose enigmas have to do with "what?", are now in the realm of hieroglyphs, like them if not hieroglyphs themselves. Some fit the "coincidentia oppositorum" of Cusa, perhaps suggesting divine mysteries and a God beyond language.

When we get to the Cary Sheet, the enigmatic allegories are further developed. There is still the "who" for the Empress, referring to Bianca Maria Sforza, bride of Maximilian. But the wing-like drapery on the back of her chair is enigmatic. The two horses of the Chariot are now wingless, facing opposite directions but looking the same way, suggesting the "Marseille" card of Noblet and the Chariot of the Phaedrus (253d-257a) now descended to earth, its horses without wings, their direction a matter of contention between noble and ignoble horses.

Star and Moon are both quite enigmatic, and with Egyptianate features. In the Star card we have high terrain in the East, like the Ethiopian source of the Nile, a sexually ambiguous Aquarius (in the Dendera zodiac, the two-jugged person was sometimes male, sometimes female); also, the five star-like planets of Fate, dominated by one star, suggest Sirius or Sothis, herald of the Nile flood, thereby also an anticipation of Christ. For the Moon we have crocodiles, pool, temple, obelisks. The crocodile, in the Greek sources about Egypt, was sometimes portrayed as evil and sometimes not. He has in his mouth the treasure typically guarded by dragons. The Bagatto's and Fool's hats both suggest Hermes Trismegistus, the legendary Egyptian sage. These are mysteries that can be unraveled by scholarly cryptography, sometimes pointing to deeper mysteries, and of which the ordinary person is in no position to know.

I don't have a sufficient feel for the other 15th century decks, as to how hieroglyphic they are and what type of hieroglyph, except to say that the Sola-Busca pips are all hieroglyphs of a more enigmatic kind. I tend to think that decks like the Charles VI are mostly a matter of understanding the cards' imagery in terms of the conventions, persons, and events of the times, some of them quite localized (i.e. "Star" in terms of particular astronomers). They mostly reflect a popular tarot, in which there is no need for subtlety. Even here, there are exceptions: I continue to find the d'Este Fool enigmatic, for example, as I have mentioned in "Bianca's Garden."

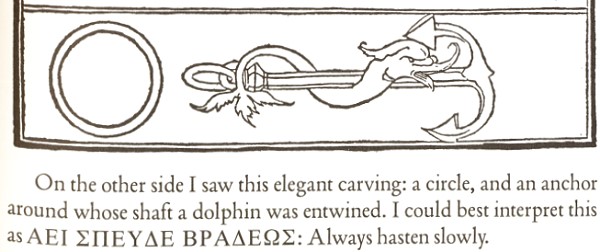

The "Marseille" designs, from Noblet to Conver, seem to me a development out of the Milan tradition. Here the cards specify further enigmas, as I have been trying to suggest in the "Bianca's Garden" section here, enigmas that only the learned can grasp. Here also, while Ficino's sense of hieroglyphs continues to exert its presence, I think a more important influence is that of Erasmus's Adagia, in the account of his first adage, "Festina lente," starting in the 1508 edition. There is one sentence in particular that sums up the method of constructing hieroglyphs that I see in the "Maseille" designs, at the end of paragraph 11. That paragraph is about a hieroglyph in the Hypnerotomachia, there rendered as "Semper festina tarde" (see below, from p. 69 of Godwin translation).

In Erasmus, I give the Latin in addition to the English because certain words may have more than one possible translation. And I encourage people to read Erasmus's whole discussion of hieroglyphs, which starts in paragraph 8 and goes to at least 14:

In the Latin, is it just literature, or the liberal arts in general, that are the "liberalium,", that enables one to read the symbolism of hieroglyphs? Either way, it is mainly books. Even the "scientific contemplation of things and natural causes" is for Erasmus primarily a matter of studying the classical literature about the thing in question, as is clear in his subsequent discussion (see link) of the circle, anchor, and dolphin of the Hypnerotomachia's hieroglyph. It is exactly that approach, I think, that the designers of tarot cards expected from one who would interpret them.Porro hoc scripturae genus non solum dignitatis plurimum habet, verum etiam voluptatis non parum, si quis modo rerum, ut dixi, proprietates penitus perspectas habuerit: id quod partim contingit solerti contemplatione rerum, causarumque naturalium, partim liberalium cognitione disciplinarum. (http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/speude/text.html)

(Furthermore, this symbolic method of writing possesses not only the greatest dignity, but also provides a great deal of pleasure to a person who can look deeply into the qualities of things; because this symbolic representation mingles the scientific contemplation of things and natural causes with the study of literature.) (http://www.philological.bham.ac.uk/speude/trans.html)

No comments:

Post a Comment